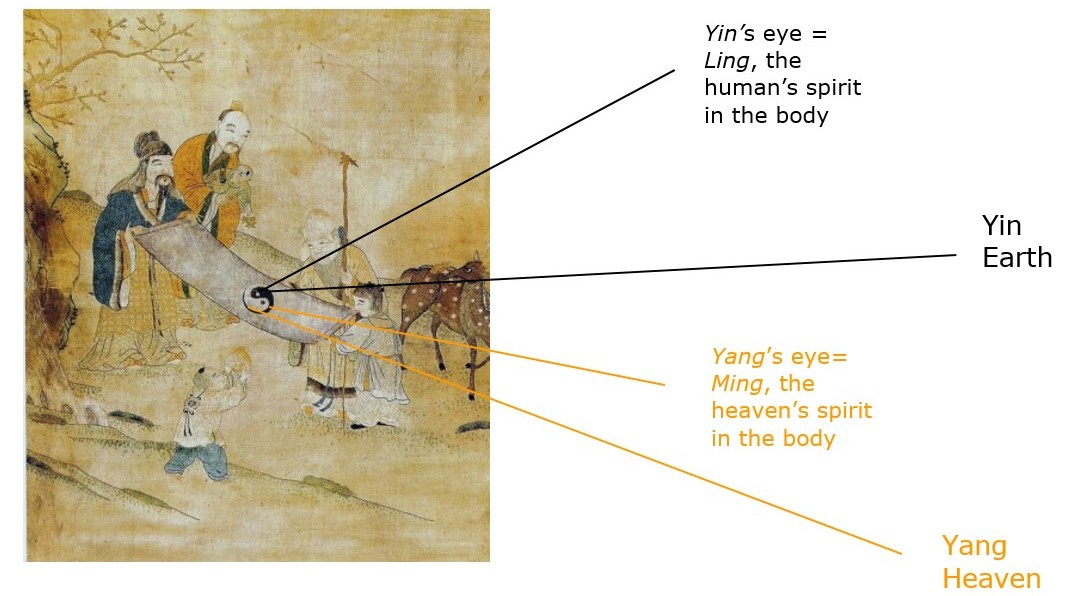

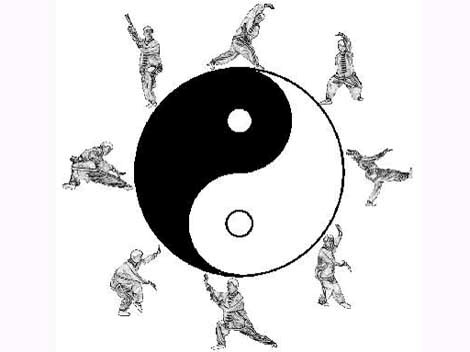

T’ai chi is represented by the ubiquitous symbol, a circle divided into two curved shapes of equal size, one being yin, the shadowed dark part (Earth), the other yang, the light part (Heaven), and together they form the Whole, outside of which nothing exists. The fall and rise of the graceful wave-line is also yin and yang, and this flow is restrained and contained by the evenness of the circumference. A touch of yin in yang and of yang in yin is indicated by the eye or seed of the opposite colour in each area (Ling/yin and Ming/yang), showing still further possibilities of change and transformation as well as depicting the flexible and sympathetic character of each to the other.

The principle of yin and yang is a fundamental concept in ancient Chinese philosophy and culture[1] observed in nature and in the environment. According to one of the earliest comprehensive dictionaries of Chinese characters,[2] this Chinese concept refers to the two opposing yet complimentary aspects of everything in the Universe, be it an object, a process or an idea. On the grand scale, yin and yang are representative of the cyclical nature of the natural world: day (yang) becomes night (yin), summer (yang) becomes autumn (yin), hot (yang) becomes cold (yin), and life (yang) becomes death (yin). Additionally, cyclic movements are expressed everywhere in our lives, emotionally, physically, psychologically, financially and in all relationships. The dance of polarities is constantly within us: to give (yang) and to receive (yin), to laugh and cry, “to be or not to be”, good would be meaningless without bad, there would be no ups without the downs; in walking there is no right step without the left; in breathing there is no inhalation without exhalation. In that way we each carry within a colourful spectrum of energies. “The mother of ten thousand things”, the yin yang concept helps with our thinking on how to develop ourselves.[3] Accepting and expressing those aspects as they are is to live with conscious integrity, in perfect balance and harmony, both in body and mind.

Neither is stronger, better, brighter or more preferable. On the contrary, the yin aspect of things is just as important as the yang because one cannot be without the other. Creating a continuous and ever-changing dance of energy in t’ai chi, the body weight shifts from one leg to the other, empty changes to full, opened to closed, awareness moves from inside to out. Hence when we move our right hand in The Form something will happen to our left hand for balancing; if some movement is generated from the outside, such as single hand ward off, something is generated by an inside force which is not manifested but is ready to be called upon at any time.

As shown in the symbol, the two opposite aspects of yin and yang are in a state of flow, creating balance and harmony – this is what we should strive for in our every day life.

[1] The earliest Chinese characters for yin and yang were found in inscriptions made on ‘oracle bones’ as early as 14th century B.C.E.

[2] Xu Shen, Shuowen jiezi, an early 2nd Chinese dictionary from the Han Dynasty.

[3] Lao-Tzu, I Ching Book of Changes, chapter 1